Franchising, retail, business

15/05/2014

Standing inside a converted shipping container, Paul Hurley, the founder of Dum Dums Donutterie, talks customers through his range of gourmet doughnuts.

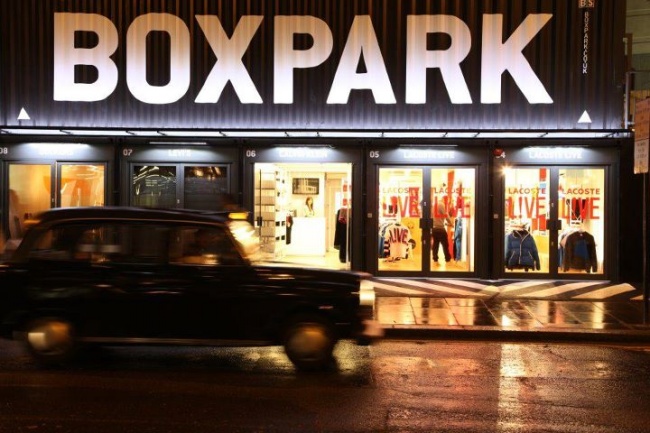

Mr Hurley sells varieties including Almond Crème & Pistachio (£3) and Crème Brûlée (£1.80) from his “donutterie” in Boxpark – a temporary shopping mall housed in containers piled atop each other, near a busy road in Shoreditch, on the fringe of the City of London.

After three week-long stints in Westfield shopping centre in Stratford, east London, last year and early this year, Mr Hurley acquired a space in Boxpark. On its first day there, Dum Dums sold out. Now, the niche company has a deal to sell doughnuts in Harrods.

Mr Hurley’s leap from east London to the upmarket department store via a shipping container is a story that could be repeated across the UK, as “pop-up stores” – the temporary conversion of an empty space into anything from a commercial outlet to an art gallery – become a mainstay of retail life. They allow entrepreneurial merchants, designers and artists to raise their profile, generate business and try out an idea before permanently taking the plunge.

“They have become not just mainstream but normal,” said Dan Thompson, an artist and author of Pop Up Business For Dummies, who has been involved in the concept for a decade.

The number of pop-ups in the UK has rocketed, although – due to their temporary nature – official figures are hard to find.

“It’s easily at 1,000 in London, if not 10 times that,” said Nicholas Russell, chief executive of We Are Pop Up, a start-up that acts as a marketplace, matching people who want temporary space with those who can rent it.

Their rise is partly because pop-ups provide an elegant solution to a persistent problem: empty shops.

In a world of high business rates, expensive long leases and the growth of online shopping, many traditional outlets have been abandoned. In London, almost 20 per cent of shops are vacant, according to Deloitte professional services. This figure rises to almost a third in northwest England.

Landlords are liable for business rates when a store lies empty – doubling the misery for those left with empty shops. “It is bad enough not receiving rent,” said Mark Rigby, chief executive of CVS, a business rates specialist. “But then you get a double whammy: you are not receiving rent – but also paying business rates.”

Pop-ups provide a cheap and handy alternative. At first popular with independent retailers and niche start-up brands, they were also the ideal antidote to Britain’s “clone town“ high streets, adding something different to a shopping trip.

Critics argue that the concept is being hijacked and commoditised by big brands, and is becoming another part of the standard retail repertoire.

For independent merchants, however, pop-ups provide a chance to sell in a proper retail setting. While the rise of websites such as Etsy – which lets people sell arts and crafts over the web – has made it easy to become an online merchant, roughly 80 per cent of retail spending in the UK still takes place in physical stores.

“When you don’t have a retail presence, it’s very difficult for you to understand a retailer’s point of view,” said Sam Farmer, who sells a range of gender-neutral toiletries aimed at young adults. Mr Farmer took part in a pop-up on the King’s Road in Fulham. Now, his wares are stocked in Space NK, the upmarket cosmetics retailer.

Companies such as We Are Pop Up have emerged to help make the process easier. The business has attracted backing from the likes of Arts Alliance, which backed Lovefilm and Lastminute.com, as well as UCL Advances, the venture capital arm of University College London. We Are Pop Up is not the only one to attract big investment. Sir Charles Dunstone, the billionaire founder of Carphone Warehouse, was one of the backers of Boxpark in Shoreditch.

But as big financial backers have started eyeing the category, so have big brands. At Boxpark, independent retailers sit alongside Nike and Puma. Even The Guardian has joined the action, launching #guardiancoffee last year, where Londoners can buy a £2.70 flat white and flick through the newspaper on an iPad.

The emergence of multinational involvement has provided ammunition for critics who argue that pop-ups have been taken over by large corporates wishing to sprinkle a hint of “edginess” on decidedly mainstream brands.

“In practice, pop-up shops – and pop-up culture – are a flailing attempt by tired brands to inject youth and vigour into something that consumers are bored of,” said Dan Hancox, a leftwing writer and author of The Village Against The World.

However, not everyone dislikes big names such as Nike opening pop-up shops.

“I love the fact that we have brought big brands down to the level where they have to pay attention,” said Mr Thompson.

By: ft.com